Nineteen seventy-five plodded on with more of the same. ‘Dr Who’, ‘Poldark’, ‘Playschool/Playaway’, ‘Dick Emery’, ‘Spike Milligan’, ‘When the boat comes in’, ‘Eric Sykes,’ ‘Love’s Labour’s Lost’, ‘How Green was my Valley’, ‘Z Cars’, ‘The Goodies’, ‘The Prince and the Pauper’, ‘Generation Game’, ‘Ain’t half hot Mum’, ‘Our Mutual Friend’, ‘Are you being served?’, ‘The Good Life’, ‘Crackerjack’, ‘Jim’ll Fix it’, and quite a few more. But we weren’t busy enough. It hadn’t been a good year financially and we went into 1976 with some nervousness.

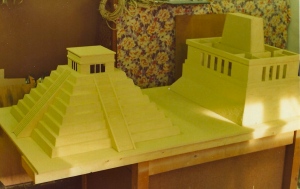

On the 14th January we went to see Leslie Fulford, the head of prop buying at Thames Television. Until then we never had to go out looking for work, it had always come to us, but we felt confident enough to spread our wings, to leave the comfort of the BBC and see how we would manage in the big wide world. We were not expecting anything to happen quickly, if at all, but by the beginning of February we were asked to make a four-foot square model of a Mayan Pyramid and a Temple, to go along side it. David Richens, the Production Designer for the children’s drama ‘The Feathered Serpent’ told us that a small boy had to hide in the Pyramid and be able to look out from between the windows at the top. We didn’t have a lot of time to do it – maybe the reason we got the job – but it seemed quite manageable. Barry and I made the basic pyramid, which had stepped sides. It would have been a lot easier if it had been smooth-sided, but, even so, it was finished with a full day to spare, apart from the four staircases that ran up each side. They were small and fiddly and were taking hours to do each one. Louise, who was getting on with them, felt worse and worse as the day wore on. Finally she left for home and went to bed with the flu. No once else was available to help finish the staircases so I asked her father Paul, a jeweller who worked for Cartier, if he could step in. We worked the whole night finishing the staircases, leaving me the next morning in which to paint the models. I had put the Temple to the back of my mind as we struggled on with the pyramid.

At about two in the morning I knew I couldn’t leave it any longer. I searched through our reference books on world architecture trying to find anything that could be made easily and could be constructed from the small amount of plywood I had left in the rack. It needed to be of a similar size to the Pyramid. Not for the first or last time, my slow but controlled panic helped to move the work along. Deadlines had to be met. There was no possibility of shrugging your shoulders and muttering ‘sorry mate’ as you blamed the shortage of materials, the weather, or anything else for holding up the work. To take it in an hour late – sometimes even minutes late – could mean holding up the whole crew, it just couldn’t and didn’t happen. By daybreak the stairs were in place and the temple constructed. They were to look like stone, so I had the morning to cover them in masonry paint before the transport arrived. They were delivered on time and everyone was pleased. We went on to do many years work with Thames Television until they closed at the end of 1992. That afternoon I had to make a giant fly swat for ‘Open all Hours’. Ronnie Barker, as Arkwright, wasn’t the only one who rarely closed.

The BBC remained our main source of income. ‘I Claudius’ and ‘The Duchess of Duke Street’ both provided us with many months of work. I made dozens of reed pens for Derek Jacobi to write the eponymous history of himself and his family, along with libraries full of scrolls and letters. There were also many cushions, bolsters and drapes for couches. We made even more for ‘The Duchess’ who ran the Bentinck Hotel in London around which the many stories were woven. In one episode we had to construct a machine to produce crisp white five-pound notes. A plain white piece of bank paper was to be inserted in at one end and the notes had to appear at the other end as you turned two small handles at the front of the machine. It was a con trick but had to look suitably ornate and impressive. After discussing how the machine might look, the designer asked Barry and me how we thought we could make it work. He had rather grand ideas for the mechanism and was rather dismissive of my suggestion that foam hair rollers, already formed with a hole though the middle, would make an easy and inexpensive way of making it work.

Two sets of rollers – on to take in the white paper and another set to spew out the finished five-pound notes from the other end – was all that was needed. It would require two handles that would make the apparatus look a little more complicated. The designer came back a few days later to see how we had got on. The device was finished and looked suitably decorative. He watched as I wound first one handle and then the second. A five-pound note appeared slowly through the brass-lined slot on the right.

‘Perfect,’ he announced, ‘how did you do it in the end?’

‘Pink sponge hair rollers,’ I said quietly, trying not to sound too triumphalist.

It was in September of the same year that we made our first film props. David Lusby arrived at our workshop – not a relation – but had been part of my early life, my father pointing out his name in the Manchester Guardian under the ballet reviews. He had danced with the International Ballet with his sister as young man, before going first into television and later films as a prop buyer. We knew of him but had never worked for him before. Over the years he gave us many iconic props to make, including the Holy Grail and Grail Diary for ‘Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade’.

He became a good friend, but for the moment all he wanted were two typewriter cases to match an original. They were for the film ‘Julia’ starring Jane Fonda and Vanessa Redgrave and were to be thrown through a window, although in the film Jane Fonda hurls the original typewriter through the window. Even so, he must have been pleased with the result for a couple of days later he came in and asked us if we could make two beds. He had found a French bed head that the director Fred Zimmerman liked but they needed a matching pair. We agreed it would be easier to make two similar ones rather than trying to copy the existing one perfectly. I don’t know what we expected but certainly not the ornately carved wooden bed that arrived the next day. It had a pineapple on each post and other carving across the back of the bed head. In later years we would have moulded much of the detail from the original bed but in nineteen seventy-six we didn’t have such luxuries as silicone rubber.

Barry set about making the basic structure and I tried to find suitable pineapples that we could use. It took me several days but I managed to track down four that came from the end of curtain rail rods and were just about big enough to do the job. For the rest of the decoration we used various styles of injected moulded carvings from a company called ‘Shortwood Mouldings’ that could be applied and painted to look like wood. We were up against a deadline as always and Barry and I were standing opposite one another at the bench gluing and fixing the last of the dozens of pieces that made up the bed head. It was three in the morning and we were both too tired to talk. I had my head down working as I positioned the last of the mouldings in place. I finally looked up to discover I was alone. Barry must have finished his bed head and had left sometime before without a word. Even his car had gone. I went home too.

‘I was bloody knackered,’ he told me later the next afternoon when he arrived after his days work doing maintenance for a local company. There was a seven-foot frame for a gong and a lever mechanism to make for ‘Dr Who’ before we went home again in the early hours.