ALL YOU NEED IS LOVE – PART ONE OF OUR STORY

The night was warm. I was walking home though South Kensington on the way back to my flat. I was twenty-five years old and I was bored. It was well past midnight on Sunday the 23rd July 1967. I had spent the whole of Saturday trying to find a girl I had met at a party in West Kensington the previous evening. She wasn’t home.

‘Maybe back later, but I’m not sure,’ her flat mate told me. ‘There’s a concert in the park. We are just about to go there,’ she said indicating her boyfriend down the hall. ‘Want to come? She might be back here later.’ She didn’t return, and I was left with ‘Whiter Shade of Pale’ still going round and round my head. It had been the only record played at the party the night before. I had arrived back in West London disappointed and wandered into The Classic Cinema in Notting Hill Gate to watch the Marx Brothers in ‘Duck Soup’. I came out later that evening feeling slightly unwell, my throat sore. It was 10.30 and I didn’t really want to go back home. My two flat-mates were away and I just didn’t feel like being alone. I wandered down to the King’s Road and saw Ingmar Bergman’s ‘Wild Strawberries’ in the other Classic Cinema. It wasn’t that unusual. I’d seen many films over the last year, usually on my own, and by 1am I was walking down Cranley Gardens towards Gloucester Road in a sort of dream. Something had to change. My life was standing still. I had no direction, no girlfriend and no money. I had no self-pity either, I was just bored. I worked as a night telephone operator at the International Exchange at Wren House next to St Paul’s but it was hardly changing my life, or my debts. I listened to my footsteps echoing down the empty street as I looked up to the windows of the mansion flats on either side of the road. Someone would open a window and call down, beckon me up, and my life would change. It had to happen before I got home.

I turned the corner into Courtfield Road still alone. I arrived at number 25, opened the door and went down the stairs into the basement. The door to my flat hung open and two young men were busying themselves trying to put back the shattered architrave. They hardly looked at me as I walked through the door. A young woman approached from the kitchen. She looked like Cathy McGowan from ‘Ready, Steady Go’.

‘Would you like a cup of tea?’ She asked me, with no hint in her voice of the lateness of the hour or the strangeness of the situation.

‘That would be nice,’ I said, ‘has anyone got a cigarette?’ I added. I might have been angry, worried, puzzled. My flat door had been broken down, but there were four women in the room that I had never seen before. I was ready for the unexpected, the surreal, anything that took away the boredom. Another of the young women came up and I felt an arm around my waist.

‘Hello,’ she said.

‘Hello. How old are you?’ I asked, feeling rather taken aback.

‘Seventeen.’ She seemed impossibly young and I turned back into the room.

There was a pretty blond girl sitting by the window in a Mary Quant dress, looking nervous, almost frightened. She smiled cautiously and I smiled back. We didn’t know then that this was the summer of love. Her name was Louise. Maybe I would never be bored again.

Forty-five years later, sitting at a table in the Savoy Hotel, I was with the same two girls. One was my sister-in-law, Yvette. The other who had sat by the window still looked a little apprehensive. She and I were about to be awarded a Lifetime Achievement Award by the Royal Television Society for 41 years of work making props for Film and Television.

The girl who offered me the cup of tea is still a great friend. I have no idea what happened to the two young men, but the door never did get fixed properly.

YOU CAN BE IN MY DREAM IF I CAN BE IN YOURS

A year later, a Monday morning in autumn 1968, Louise and I are working together set dressing a barn in The Playhouse, Walton-on-Thames. It is for an amateur production of ‘Johnny Belinda’. She had just started as a design assistant at BBC television and I was still working nights as a telephone operator. The set had been built and we worked for two days making the bare bones of the structure look like an old decaying barn, filled with the farm props the group had borrowed from a local farmer. Bales of straw, horse harnesses, tools, old wood, sacks, the decaying detritus of the several out buildings, all went into the mix, making the set not only look authentic but smell authentic too. I loved it. I imagined this was my life; that Louise and I spent our days recreating things, playing from early morning until evening, enjoying ourselves. I knew it was unreal, that no one could do this for a living, that I would be back in my seat in Wren House after my few days off. That had its interest too; putting calls through to Tel Aviv during the Six Day war, when no one, even the frustrated and angry journalists were allowed more than three minutes because of the limitations of time and the channels available. Next to you the Cairo channel, where calls were difficult even to connect; the temptation to greet the operator with ‘shalom’ growing as your frustration built with the difficulty of getting any calls though at all.

I once put a personal call though to a scientific station some way from Goose Bay in Canada. I never found out where it was but I was quite pleased with myself after going through several operators including wireless connections to the remote station. The man I was trying to contact wasn’t there. I explained to the woman trying to contact him that I could try again later for no extra charge. She insisted on being put through to the person who had answered, even though it meant I had to charge her from the time she started speaking. She spoke for about nine minutes and then hung up. I wrote up the ticket and rang her back with the charges.

‘Give me your supervisor, the man I asked you to get wasn’t there.’

‘Yes I know. I said I would have tried it later for you.’

‘I’m not paying. He wasn’t there.’

‘Yes I know. The charge would only have been one pound ten shillings and I could have tried many times for that. But you wanted to speak to them yourself rather than me doing it.’

‘Give me your supervisor.’ I passed it over to him. As usual it was more cost effective just to reduce the amount rather than get into some lengthy correspondence. I forgot all about it until one night shift when I was called over by the supervisor and asked if I had been the one to put the call on. I had nothing to hide and was still rather pleased I had even managed to get through to them.

‘The problem is Keir, we don’t have a service to wherever it was you put it through to.’

‘Wasn’t it Canada then?’

‘No, that’s the point. You just went through Canada. God knows where you ended up, somewhere in the Arctic I should think. Don’t do it again. There’s been hell to pay.’

‘Oh, so no medals for my ingenuity then.’

‘No. Now bugger off and get back to work. And try and stick to places that exist. Otherwise …’ I went back to my least favourite job.

‘Bookings. Can I help you?’ You got to write out a ticket, pass it on to someone else, and that was it. All night.

One night in August 1969 I put a personal call on from the Isle of Wight to New York for a Sarah Dylan. Her last name and the location left me in no doubt as to who would be making the call. Such excitements were few and far between.

PARTNERS

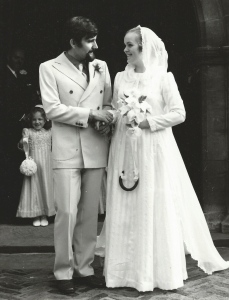

Louise and I were married on the 16th May 1970. Louise made her own dress and those of the three bridesmaids. By the time we married she was already an assistant designer at the BBC and the night before we married I gave up my job at the International Exchange.

Our wedding day with Clare, Louise’s god daughter aged five who would later work with us in her holidays.

We set up home in Surbiton in a one bedroom flat at the top of a three-story house, its windows overlooking the tops of trees. No one lived in the flat beneath and on the ground floor was a business so we had the place to ourselves most of the time. Being out of work I busied myself painting the flat and helping a friend with his house for ten shillings an hour. I had applied for several civil service jobs and was enjoying myself while I waited for a response. A few months had passed and Louise thought it was time for me to present myself to the Employment Exchange. One Thursday morning she dropped me off at Kingston upon Thames and waited in the car. Some time later I emerged feeling dazed.

‘I start tomorrow at Hammersmith Employment Exchange,’ I told her. ‘There is a new intake course on Monday and they would like me to spend at least a day in the Exchange beforehand. The man who had interviewed me asked why I hadn’t applied to them when thinking of a career in the Civil Service.

‘With your qualifications you should be this side of the counter, don’t you think?’ I hadn’t thought about it but found it hard to disagree. Louise was delighted that finally I seemed to have a proper job.

My time at Hammersmith went quickly. Louise, who was working up the road in Television Centre in Shepherds Bush dropped me off in the mornings and picked me up on her way back from work. I sometimes walked up the road and spent a little time in her office at the BBC. Life was easier in those days, you could come and go without the need for constant security.

I must have found favour as six months later I was sent to the brand new Government Training Centre at Twickenham, right next to the Rugby Ground, as their Placing Officer. The first trainee was due to leave at the end of my first week. The previous Placing Officer, who had been used for other duties while the Centre had been getting on its feet, had taken fright and left. Understandably the instructors were none too pleased that nothing had been done to give their trainees a good start in their new careers. One hour in, on that first Monday morning, I was faced with the huge frame of the centre-lathe turner instructor looming over my desk. A Viking with a big bushy beard, his controlled rage at the lack of any job in the offing for his new trainee, made me understand that the buck was going to stop with me. I might have been one of the few Grade six civil servants with his own office and the ability to organise his own time, but I had to deliver. Three days later I had managed to get the trainee a job that the Instructor approved of. It was the first trickle of a growing river of eager engineers, plumbers, carpenters, bricklayers, spray painters, mechanics, that passed through my office in the next months and years.

I was still at Hammersmith Employment Exchange when we did our first paid work for the BBC under my name, Keir Lusby. Louise was working under her maiden name, Louise Vanson, and was the designer on Playschool.

She had already made several models for the show and felt it was part of her job to provide them, but when they asked for twelve models, depicting the twelve days of Christmas, as itemised in the song of the same name, she felt that the work involved would be over and above the normal requirements of the job. She could not be paid under her own name so we invoiced it separately under my name. As November 1970 progressed, it was a taste of things to come. Our one bedroom flat became knee deep in paper and card of all colours. The models were paper sculptures decorated with metallic, hand printed ribbons made in India. They came from Paperchase, a wonderful new source of materials in Tottenham Court Road. Also from Kettles, a large cavernous shop situated in a former bank in Holborn, full of every type of paper and card, including boxes of many shapes and sizes, ready for decoration. Louise as an art student had been able to buy a single sheet of tissue paper from the myriad colours available. It was hard to believe that the twelve small sculptures that resulted from all our hard work could have made such mountains of waste paper, that grew from the small neat carrier bags that we had arrived home with, to several dustbin bags we had to dispose of. It was something we were going to have to get used to. We got paid just under six pounds a model and had to wait nearly six months for our money as the BBC was on strike, by which time we were working on props for a brand new show – The Goodies.

So, that’s how it all began. I did wonder.

LikeLike

Next time, how it all carried on. It’s still a wonder to me.

LikeLike

I am really delighted to read all about your beginnings. Fascinating. More to come, which I know I will enjoy.

LikeLike

From the young woman who audaciously put her arm round your waist, thanks Keir for giving me back so many wonderful memories. Yvette

LikeLiked by 1 person

As someone who made rubber stamps for Keir Lusby over several years of working at Enkay Press in Byfleet in Surrey. I was saddened to see that K/L had to finish trading after 40 or so years trading.

One stamp I made was for ‘Boot in The Door’ for Spitting Image. It can be found on the opening titles.

Other items I made was two gold bars for Watchdog where a man gave fake bank drafts in exchange for the gold. When the ‘bars’ were placed in the brief case on papers they hardly made a dent as they were so light. Many other stamps were made by me for K/L . Wishing you Keir and Louse all the best wishes for the future.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Andy, thank you for remembering us. We both remember Enkay Press as one of the local companies who helped us a lot. You could always be relied on not to let us down, either in quality or speed of delivery. As you say we needed your help many many times and you never once said no. Although we are sure there must have been occasions when you said ‘You want it WHEN?’

LikeLike

I remember Keir Lusby very well, from when I was a motorcycle courier in the early 90’s for Point to Point couriers. Yours was a very interesting place, with all sorts of creative stuff going on. Plus everyone was very pleasant, unlike many calls we had.

Some of the items I collected & delivered for you were pretty amusing too, & weren’t the norm. i.e. A box of plastic sharks from Hamleys. A mock cermonial sword to the BBC at the TV centre, & I remember carrying a sack of plastic oranges out of town, & having to put up with cabbie’s saying ‘feeling fruity are you’ at every set of lights.

I’m sure it was for yourselves that I was tasked with finding a bull whip when I was in the West end one day. It was amusing to go into a sex shop in full leathers….I never knew there were so many different types! 🙂

The best of luck to you both.

LikeLike

Thank you for getting in touch. We used Point to Point Couriers for many years and always had a good relationship with them and all the drivers both motorcycles and vans. We were always grateful to be able to get things we needed – usually at very very short notice – but didn’t always appreciate how tricky some things were to deliver or collect from other suppliers. We were never let down despite horrendous traffic conditions sometimes, not to mention the rain and snow! So thank you Stewart. I don’t own a motorcycle but had a quick look at your website http://www.stewarts-motorcycles.co.uk and enjoyed reading it. From the many testimonials you have there it seems you are still providing an excellent service.

LikeLike